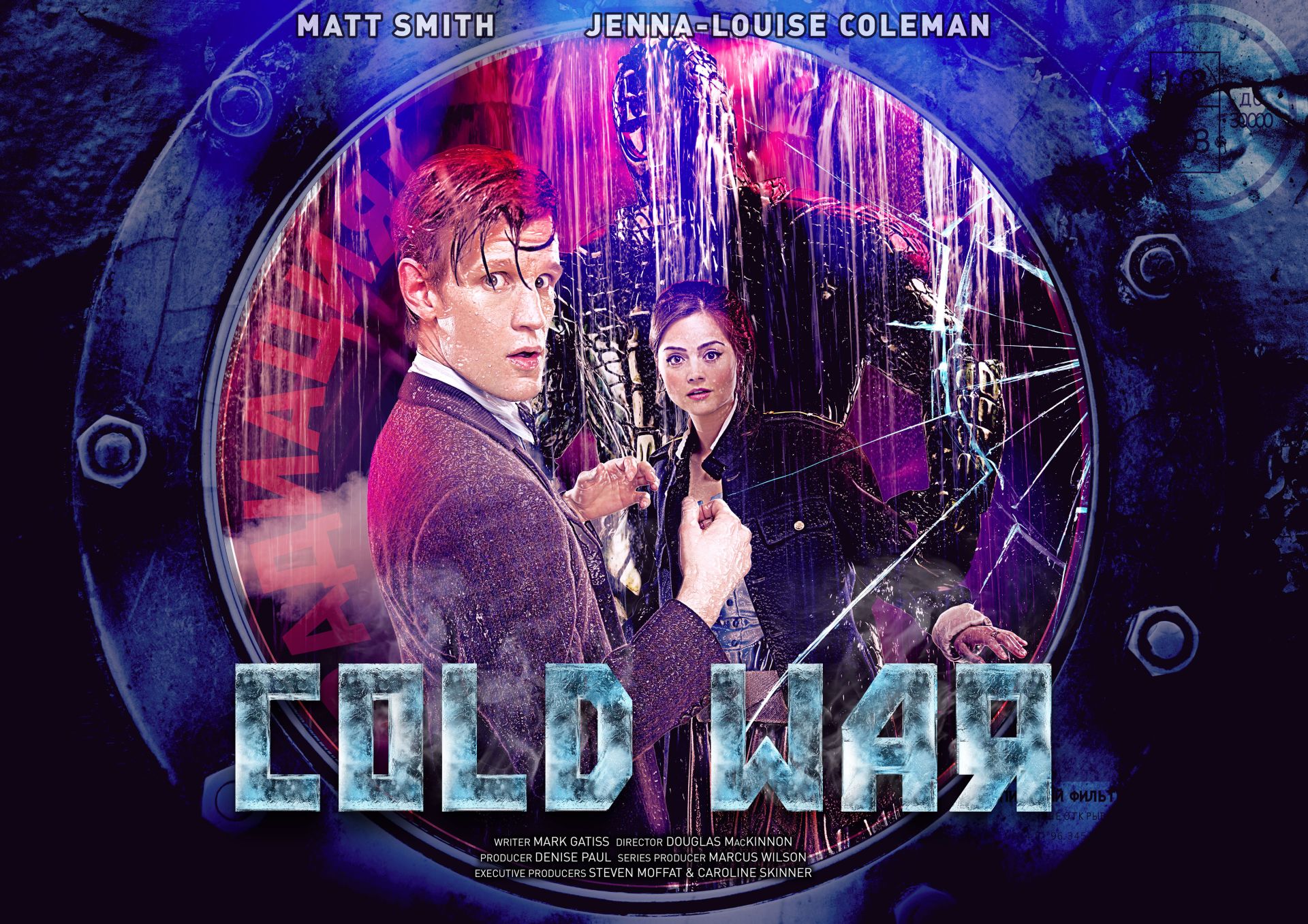

Cold War

Sunday, 14 April 2013 - Reviewed by Matt Hills

Doctor Who - Cold War

Written by Mark Gatiss

Directed by Douglas Mackinnon

Broadcast on BBC One - 13 April 2013

In the promotional build-up to this episode it seemingly became compulsory to make jokessssssss about the Ice Warrior’s sibilant speech patternssssssssss. So, now that’s out of the way, how successfully did this week's Who reimagine the Martian race? Mark Gatiss’s script was determined to depict them as a terrifying and plausible threat. As Clara says at one point, “it’s all got very... real”, and that could almost have been the mission statement of 'Cold War', where monstrous realism was the order of the day.

Instead of clunky design, the Ice Warrior’s “shellsuit” is shown to be body armour with an extremely useful line in sonic remote control. And we get the same Alien-style trick used all the way back in 'Resurrection of the Daleks' – the not-quite-seen entity out of its housing and busy stalking its prey. It’s unsurprising that ‘Dalek’ has instantly become a reference point for this adventure – the lone, reimagined creature in a lock-down situation makes comparisons too tempting to resist. But however many similarities can be drawn between ‘Dalek’ and this ‘sub-under-siege’ scenario, there is one vital difference: Rob Shearman’s much-redrafted magnum opus never punctures its sense of reality.

By contrast, ‘Cold War’ unwittingly stresses its artificiality right from the outset. The decision to depict a Russian submarine’s crew speaking English from the word go emphasizes a profound tension between narrative reality and production anxiety – clearly it was felt that Russian voices and subtitles would frighten off the early Saturday evening audience. We get a production decision which assumes the worst of its audience, rather than crediting them with curiosity and intelligence, because the English-speaking opening sadly can’t be rationalized through any TARDIS intervention. It’s a production choice, pure and simple, indicative of how weirdly mixed-up and inconsistent this episode becomes. Text is given in Russian-style lettering in the submarine, as if to remind audiences of the setting (in case they’d forgotten), yet this doesn’t clearly correspond with previously established TARDIS continuity either. It’s all a bit of a linguistic tangle, where playing-it-safe production decisions are constantly screamed out, puncturing the sense of immersive reality that a base-under-siege story absolutely calls for. Given how brilliantly TARDIS translation was handled in, say, ‘The Christmas Invasion’, where a sudden shift into English corresponds with a punch-the-air moment and a vital plot point, this episode sadly missed its chance to show us the TARDIS translation matrix kicking in, in what could have been a truly startling, stunning instance of the Doctor’s Time Lord powers. Imagine if suddenly, just as the order to launch a nuclear missile was given, we’d shifted from subtitles into spoken English. What could have been a stone-cold classic Who moment, transforming Russian characters from exotic, stereotyped others into our trustworthy protagonists, remains something that can only be imagined on Saturday night telly.

For me, the 1980’s music references were also clumsier than a 1960’s Ice Warrior costume. Despite David Warner’s strong performance, and he even made the query about Ultravox’s break-up work brilliantly, his character was lumbered with a habit designed to reinforce the eighties’ setting. I think this patronized the audience yet again – can’t we recall that it’s the eighties from an on-screen caption, talk of nukes, M.A.D. and mention of shoulder pads? Do we really need ‘relatable’ pop references to ram the time-frame home? Professor Grisenko was certainly an eccentric, but he felt too much like a designed creation rather than a flesh-and-blood character: blatantly there so that the “song” theme could get its pay-off via Clara’s Duran Duran rendition. Pop music was crow-barred into Chris Chibnall’s ‘42’ (hardly a fan favourite), but its inclusion here is no more convincing, I’d wager. Again, the reality effect worked so strongly around Skaldak is undermined by some of these surrounding decisions.

And if the Ice Warrior out of its shell is a scarifying highlight of the story, helping to ramp up the tension by playing to Gatiss’s formidable strengths as a writer, whilst also benefiting from sympathetic direction and lighting, then the choice to reveal Skaldak’s face feels a little misguided. It slavishly emulates a horror genre template: the big reveal of the bravura monster effect, after a lot of tantalizing and audience anticipation. But in this case, the effect wasn’t spectacular enough to warrant the reveal, and I think the mystique of the Ice Warriors, as well as Skaldak’s presence, would have been better served by refusing to give the audience this visual FX reverse shot. If we’d only seen the Doctor through the Martian’s eyes, without ever glimpsing what turned out to be Skaldak’s rather generic appearance, then that very absence would have been infinitely more thrilling and unsettling. By following the established plot beats of a literal face-off (even seeming to playfully reference Moffat’s “don’t blink” via a contest of wills) Skaldak and the Ice Warriors were diminished a little, when previous events had industriously set out to achieve the exact opposite.

There’s much fan-friendly stuff to welcome here: impeccable model FX work on the sub; HADS gets a mention (though wouldn’t that have been better explained earlier in the story rather than at the very end?); and (this) Clara treats her first historical outing as a test of her own performance, in a rather touching and well-played device where she constantly seeks reassurance. ‘Cold War’ has atmosphere in abundance, and is consistently well acted by all of its cast, with Liam Cunningham deserving just as many plaudits as David Warner. It also has a cleverly integrated bit of business about Skaldak’s singing – paralleled with Ice Warrior sonic technology – and his own family relationships. He has a daughter, so in the sentimental codings of family entertainment, we know right away he can’t be an irredeemable monster. And given that Skaldak doesn’t definitively leave until immediately after Clara’s singing, I interpreted her effort as reminding him of his daughter’s songs (indeed, Clara had already emphasized the link to “daughters” in dialogue). The new romantics save “Planet Earth” (why couldn’t that have been Grisenko’s favourite? “looking at planet earth… this is planet earth”). Clara’s emotional intelligence and resourcefulness are neatly reinforced here.

But the Doctor appears to rather strangely teach Skaldak, and by implication us, that nuclear deterrence is basically A Good Thing, and that mutually assured destruction handily works to keep the peace. I can’t help but feel that these aren’t unquestionably Doctorish ideologies, and I wonder if this section of the script underwent many revisions or generated much in the way of contention across the production process. It wouldn’t have been like this in the days of the Virgin New Adventures, I suspect. Further back in time, in 1984, Doctor Who mounted a version of this story as science fiction allegory (‘Warriors of the Deep’). The intervening years mean that ‘classic’ allegory can now be safely tackled as ‘new’ popular memory, swapping one kind of distancing shell for another.

‘Cold War’ is an incessant conflict between two power blocs where neither can entirely triumph. Intended realism fights against (unintended) displays of production artifice, and what is very nearly a chilling classic finds itself marred, though not sunk, by specific production decisions. The Ice Warriors are now a more complex and convincing on-screen race than ever before, but this particular Ice Warrior hero finds himself encased by narrative techniques (especially the language issue and the pop song gimmick) that threaten to jolt audiences out of Gatiss’s finest sub-under-siege storytelling, despite all its dripping, dripping water and its damp, desperate physicality.